By DJ DiDonna, LEO Board Member

Black Americans are 3.6 times more likely than whites to die from COVID. For many, the novel coronavirus tells the same old story: people of color are chronically worse off than white counterparts in their own country.

It is impossible to talk about solving poverty without first understanding the role that race plays in inequality. It undergirds every study, partner, and focus area from LEO’s eight years in existence, from education to employment, from housing to health, and from criminal justice to well-being and self-sufficiency.

LEO exists to empower stories about poverty solutions with evidence. As this year comes to a close, we’d like to share what we’ve been learning about race and inequality from our research, our nonprofit partners, and those experiencing poverty themselves.

When Dr. Karla McCullough was pregnant with her first child, she told herself—and anyone who’d listen—that it was a girl. It had to be. Even though as a Black child in Mississippi her teacher said that her “straight-A’s were wasted on her.” And even though Black women are more likely than Black men to be stuck in the cycle of poverty.

Why? Because Karla knows that it’s dangerous to be a Black man in America. One-third of Black men will spend time in prison in their lifetime; one in eleven are currently under correctional control. Even if a Black man lives a fully law-abiding life, he's more likely to get pulled over, wrongfully prosecuted, or like so many famous Mississippian civil rights leaders Karla grew up admiring, killed.

Karla cried when she found out that her baby was a boy. She was excited and grateful, of course, but she feared that her son’s story had already been written for him.

So she decided to do something about it.

Decades later, after two degrees from historically Black colleges and a successful corporate career, Karla is the Executive Director at the Juanita Sims Doty Foundation (JSDF). JSDF is changing the narrative about children of color, specifically Black boys and young men.

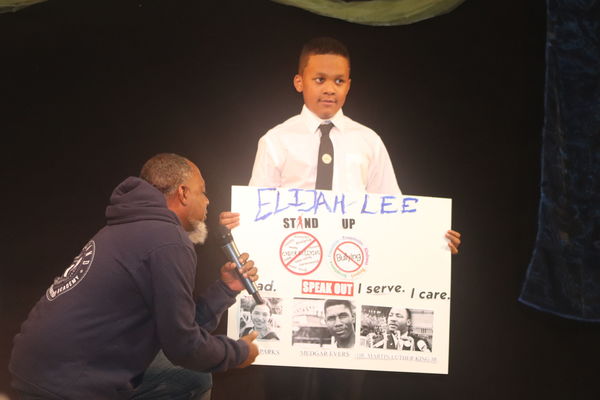

JSDF’s core program, Ambassadors of the Evers Academy for African American Males, (A-TEAAM), is based on the research around the dehumanization and racialization cycle that Black Americans—especially males—experience. Karla credits a series of mentors throughout her life with helping her persist through negative messages about herself and her potential; JSDF’s A-TEAAM provides that at scale. The program brings together a “village of mentors,” providing skills, training, and support at a crucial age. It seems to be working: A-TEAAM members show increased school attendance and exhibit positive behavioral changes.

But Karla wants to validate and scale their approach outside of their hometown of Jackson, Mississippi—for middle schoolers everywhere. JSDF is part of one of LEO’s most recent cohorts of nonprofit providers seeking to evaluate innovative solutions to poverty. Together, LEO and JSDF are working to figure out which parts of their program are the most effective, even in the midst of the pandemic.

Halbert Sullivan lived the story that Karla feared for her son. Halbert spent over two decades of his life addicted to drugs, in and out of prison; a victim of what he calls his own “bad choices.”

At 43, Halbert was “sick and tired of being sick and tired.” He went directly from his drug rehab program to a local community college. Within a few years, he had graduated from the prestigious Brown School at Washington University in St. Louis. Now over 27 years clean, Halbert is the Founder and CEO of the Fathers and Families Support Center in St. Louis, dedicating his career to shaping the lives of young Black men.

Sullivan’s Fathers and Families Support Center (FFSC) sees the family unit as key for this transformation. There are 24 million children who grow up in fatherless homes in America—75% of whom are people of color. A whole host of problems stems from this. The financial uncertainty of a single-earner household is often solved by taking on more than one job or one with longer hours. This results in less quality time with one’s parent. Young women from fatherless homes account for 82% of teenage pregnancies. Children from absentee-parent homes are at least twice as likely to exhibit behavioral issues, run away from home, and commit suicide.

Halbert’s solution: a “check up from the neck up.” FFSC aims to change self-perception, to repair some of the emotional and psychological damage caused from growing up in a single parent household. It also delivers hard skills like literacy and a GED. FFSC participants endure six weeks of intensive daily curriculum. They learn how to dress for professional environments, how to budget, and—perhaps most importantly—what it feels like to be emotionally supported for the first time in their lives. Sullivan believes that this support is the Trojan horse of the model; where else do we expect those from fatherless homes to figure out how to be good parents themselves?

FFSC’s approach appears to be working, and the news is spreading. One of their marquee programs, which focuses on preparing felons set for release for the job market, has seen its graduates placed in jobs at the same rate as those without criminal records. LEO and FFSC have partnered to help understand which aspects of the intervention are the most effective. Armed with this evidence, Halbert seeks to scale his approach nationwide.

For LEO research faculty member David Phillips, the story of racial inequality is most easily seen through housing and transportation. Housing is also the most visible proof of inequality, David believes: “We either walk by neighborhoods, or we don’t.” The evidence of the tragic impact of housing policies on future outcomes for Black Americans is best told through the story of “red-lining.”

In 1933, the federal government established the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) to attempt to limit foreclosures and stabilize the housing market in the wake of the Great Depression. Part of the goal of HOLC was to help lenders evaluate risk so that they could, in theory, better distribute funds for home ownership. In the process, neighborhoods were evaluated based on a variety of characteristics, such as housing age and price, but also the race and immigration status of their residents. The borders between the “riskiest” neighborhoods and those with moderate risk were drawn with red and yellow lines. What resulted was a systematic denial of credit for those in red-lined districts—overwhelmingly people of color.

Almost a century later, the impacts of these policies on the poorest Americans are just starting to become clear. A recent working paper from economists at the Chicago Federal Reserve found significant differences in “house values, rents, vacancy rates, and segregation” due to red-lining. Crucially, the approach also resulted in decreased homeownership among Black Americans which persists to this day. According to a report by the Urban Institute, the current gap between Black and white homeownership is larger today than it was when red-lining was standard practice.

This has had a material impact on the so-called “wealth gap”: the average white American family has ten times as much wealth (~$117,000 versus ~$17,000) as the average Black family. David Phillips and others have shown that a lack of wealth naturally hinders one’s ability to climb out of poverty. But the other lasting impact of red-lining? Longer commutes.

Research shows that geographic distance between where one lives and where one works—called “spatial mismatch”—disproportionately impacts minorities. Spatial mismatch not only results in more time spent getting to work—and therefore time away from one’s family—there’s also evidence that employers discount job applications based on distance from one’s place of work. In one of David’s studies, he found that offering a public-transportation subsidy significantly increased the chances of employment for job searchers, who were primarily lower-income Black Americans in Washington, D.C.

LEO looks to help communities respond to the legacy impacts of housing discrimination. The results of a recent study in Seattle suggest that transportation subsidies can start to erode some of the blockages. As part of David’s ongoing work with King County (Seattle), LEO has found that giving lower-income residents free public transportation can have a positive impact on well-being and even access to credit.

LEO’s mission is to turn research into action to help people move permanently out of poverty. We’re in a unique, but also tricky, position to do so. As part of an academic institution—the University of Notre Dame—we are often very different from the population we serve. Our staff is predominately white and our field—Economics—lacks diversity, especially among those with advanced degrees. We face an impossibly steep learning curve to understand the realities on the ground for our nonprofit and government partners. Which is precisely why we rely on them as partners.

Working closely with partners like Karla and Halbert inspires us at LEO to fight for the conditions that enable all Americans to break free from poverty. We are committed to helping poverty’s fiercest adversaries back up their stories with evidence, and begin to change the story of equality in America.