In a program designed to reduce costly hospital readmission rates but largely written off as a failure, LEO co-founder Bill Evans saw a pathway to improve health outcomes for low-income people through the innovative approach of four Chicago hospitals.

Hospital readmissions are costly to patients, hospitals, and the government. Unscheduled 30-day hospital readmissions generated about $23 billion in costs to Medicare in 2017 alone, which Evans calls “a staggering sum of money.”

These high costs are partly due to the fact that one group with high readmission rates are people known as “dual-eligibles.” Dual-eligible people are insured by both Medicare and Medicaid—the latter covering any cost-sharing required by Medicare. People of color also tend to have high readmission rates. Both groups tend to have relatively low incomes and poor health, making them especially susceptible to a cycle of illness, hospital admission, unexpected medical expenses, and time away from work and family.

“Just think of simple situations,” Bill says. “You are in the hospital for three or four weeks because you had a fairly serious condition. You come home. There’s no food in the refrigerator and you’re too sick to go get it. Or you’re too sick to pick up your prescriptions or you don’t have anyone to take you to your follow-up appointment. These aren’t necessarily medical issues; they’re just life issues.”

But life issues can affect health and the ability to recover from a hospital stay at home. To help hospitals keep their readmission rates low, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid created a large grant program known as the Community-based Care Transition Program (CCTP). CCTP funds give health care providers the resources to develop and run transition care programs at their local facilities. With few parameters around how these programs should be structured or operate, over 100 different versions of CCTP programs sprung up at health care facilities across the country. Eighty of them, however, closed after their initial CCTP grants were not renewed, as they showed no reduction in 30-day readmission rates.

But Bill was not ready to give up on the potential of transition care programs just yet. He was intrigued by a CCTP program he had heard about in Chicago, a collaboration of four Chicago-area hospitals called the Chicago Southland Coalition for Transition Care. What made this program stand out? The Chicago coalition’s CCTP program was developed in conjunction with Catholic Charities Chicago. Unlike most other programs which were staffed by medical professionals, the Chicago program used social workers to help patients make the transition from hospital to home.

“They were trying to attack a particular problem,” Bill explained. “The notion was that, for people who are readmitted to the hospital, a lot of times the problems are generated because things that happen in their day-to-day life were preventing their recovery.”

Social workers are trained and equipped to help with some of those life problems that medical professionals may not know how to handle or even ask about. Social workers can help people get rides to their check-ups, access nutritious food, or make sense of lengthy aftercare instructions.

“To be frank, most of the CCTP programs that were developed, we didn’t anticipate that they were going to actually work. All they were doing was calling people on the phone and saying ‘How’s it going? Do you need anything?’,” Bill said. “That type of light-touch intervention is probably not going to make a difference in this context. Especially when what someone needs is a ride to the doctor or food in the refrigerator.”

Despite the failures of the CCTP program as a whole, the Chicago-area program showed promise despite the challenges the coalition hospitals faced. They were already on a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid watchlist because of their high readmission rates. They were also all located in high-poverty, predominantly non-white areas of Chicago—both predictive factors of high readmission rates.

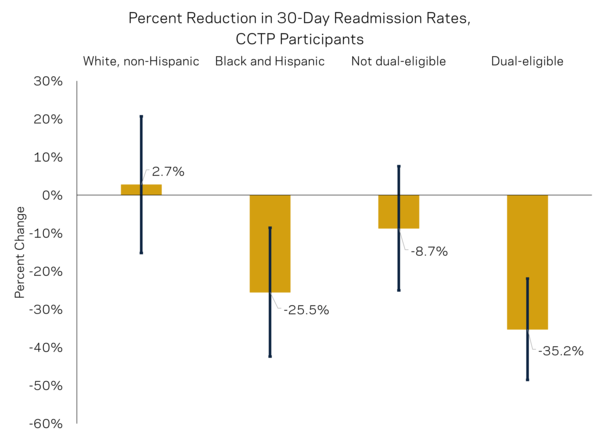

Bill wanted to investigate the promise of the Chicago social-worker model, and the difficult circumstances the hospitals faced make the results of the study Bill launched at LEO even more compelling. He and his research team found that Chicago’s CCTP program was successful at reducing readmission rates, and that most of the reduction in readmission rates helped two very vulnerable groups: people who were dual-eligible and people of color.

This accompanying figure illustrates that white patients, who as a group have below-average readmission rates already, benefit very little from the CCTP program. Black and Hispanic patients, on the other hand, benefit greatly, with a reduction in readmission rates of about 26%. We see the same trend when we look at dual-eligibility. Those who are not dual-eligible see a slight decline in readmission rates, but it's not significant. But dual-eligible patients see a 35% decline in readmissions when they are part of the CCTP program. This is one of the more exciting results of LEO's CCTP study—the program reduces health disparities.

The drop in readmission rates also translates to reduced costs. The Chicago CCTP hospitals saw a 32% decrease in 30-day readmissions costs. When the reduction of 60- and 90-day readmissions are also factored in, the program reduced readmissions costs by approximately the full cost of providing the program. The fact that the social worker-staffed program seemed to work for a wide variety of people indicates that it may be an effective and flexible strategy for hospitals to meet their readmission rate goals.

Bill elaborated on this idea: “Suppose your readmission rates are high for a particular group. You could target this program to them. What the Chicago CCTP program seems to do is reduce the really expensive readmissions. So, if your goal is to reduce readmission rates overall, you can apply it to a large group of people. If your goal is to reduce costs, then you really want to concentrate on the expensive readmissions—the people who have very difficult procedures, longer stays, more expensive treatments.”

For the quality and significance of their results, Bill and his research team—two of whom hold PhDs in Economics from the University of Notre Dame—were recognized as one of only five finalists for the National Institute for Health Care Management's Research Award.

“NIHCM is an organization that is dedicated to evidence-based solutions for our health care system,” Bill explained, “and so it’s intellectual tie with LEO is pretty high. We’re honored that we were finalists for this award. Not only does it recognize the importance and the quality of the research, but it’s also from an organization that cares about the same things we care about: helping others and using data to determine what programs work and which ones don’t.”

Bill has spent the last 25 years performing health care research. He initially entered the field so he could learn more about the health care system and help graduate students find jobs in the private sector doing health research. He stayed in the field once he realized the research potential it offered.

“The one aspect of health that is interesting is that there’s a lot of plentiful data and it’s a highly regulated sector. As a result, there’s just a lot of opportunities to answer interesting questions,” Bill said.

Those years of experience conditioned Bill to continually seek to understand what is working about Chicago’s CCTP program and how it may be replicated elsewhere. LEO’s research is significant for both the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid’s policy goals and improving health outcomes for people who have historically struggled with poor health and scant financial resources. Bill is hoping to expand the scope of the study by running a large-scale randomized controlled trial across five or six communities.

He explains his proposed study as “a heads-up test between social workers and medical professionals in terms of running these care transition programs. That would be the experimental run, where you randomly assign people who are being discharged a medical professional or a social worker, and you actually see where the advantages are.”

The Chicago CCTP program could provide valuable insight into how to improve health outcomes for some of the most medically vulnerable populations receiving treatment at hospitals nationwide. But more research is needed.

“That would be my goal for this research,” Bill said. “To make sure that it doesn’t just sit on the shelf, but that we learn something from it and disseminate it to other partners who can use it to serve their communities. That’s the way it works at LEO. We put our research into action.”