As the first months of 2020 unfolded, policymakers scrambled to craft the appropriate economic response to a once-in-a-century pandemic. The scale and scope of their response was, of course, unprecedented. But for nonprofits across the country, the questions being asked were actually very familiar: how much do we give, to whom, and in what way?

After the nearly $2 trillion CARES Act was passed, the nonprofits tasked with distributing their slice of CARES Act funding prepared for the impending flood of money and clients. But they also faced an existential dilemma: the money was meant to go directly to those in need, not to build capacity for those distributing it. Perpetually stretched and under-resourced, nonprofits had to find a way to prevent people from entering into poverty in the first place, let alone survive as an organization.

One of the most promising approaches to stopping poverty before it starts is called emergency financial assistance (EFA). Instead of providing services for those already experiencing homelessness, malnutrition, or medical emergencies, EFA grants target those most vulnerable to these conditions before it’s too late. LEO has partnered with innovative nonprofits across the country to understand how EFA can improve outcomes, save money, and help rewrite the playbook on fighting poverty.

What is EFA?

Over time, the American government has created safety nets for the basic needs of citizens that need help supporting themselves: food, housing, and health. But little exists to help those in urgent—though temporary—need. For example, funds to help with a rent payment to stave off eviction, or money to fix a car needed to get to work.

Nonprofits across the country seek to fill the everyday gap in the federal safety net through EFA. EFA payments can range from hundreds to thousands of dollars, and can be made directly or indirectly, via cash or in-kind payments, (e.g., rent directly to landlord or towards a utility bill). But there’s little information on exactly how much is given across the country, to whom, and how.

A survey identified over $300 million in annual EFA among Catholic Charities chapters for items such as rent and utilities, and the United Way of America reported it receives more requests for emergency help with shelter and utilities than for any other issue: 4.4 million calls each year. Partially, the issue is structural—it’s easier to track federal dollars, such as unemployment insurance or disability insurance, than to trace a mosaic of city and local providers of aid.

As a result, there’s limited evidence on how well EFA works, let alone which ways to provide it are more or less effective. One of the few rigorous studies on the topic was led by LEO in 2016. LEO studied Catholic Charities Chicago’s Homelessness Prevention Call Center (HPCC), a city-wide hotline available to anyone in need of “short term help.” Upon qualifying, callers were given up to $1,500, depending on their need and the purpose of the funding.

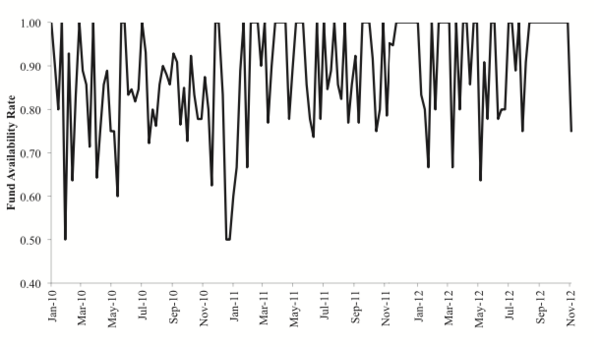

In addition to the novelty of using the 3-1-1 hotline to combat homelessness (it’s typically used by cities as a more civic informational catch-all), the call center’s approach had another unique feature which attracted LEO’s interest: unpredictability of available funds. While the information and counseling the call center employees offered stayed constant, Catholic Charities Chicago’s ability to give to callers varied significantly, depending on the availability of funds on that day. This volatility (see the accompanying graph) led to a natural experiment of sorts, meaning that the study could be done quickly, and using past data.

For Catholic Charities Chicago, it meant getting quick feedback on how well its approach was working. LEO’s study showed that people who called when funding was available were 76% less likely to enter a homeless shelter in the following twelve months, and were arrested for violent crime 51% less often than those for whom no funds were available.

Not only was LEO able to produce a rigorous study showing the effectiveness of the hotline, the findings found their way into the public eye, and spurred the launch of a dozen additional studies on EFA across the country. These additional studies seek to answer a few important questions about giving targeted aid to those in need.

What’s the best way to give?

A perhaps surprising dilemma facing nonprofits is how to even give out all the money they receive. Coming back to the CARES Act, many nonprofits have struggled to meet the increased demands of their clients while also ramping up services. Part of this issue stems from the logistics around how the funds are administered. Historically, financial assistance is often given indirectly to the client in need, for example to the landlord or the utility company for missed payments. But an emerging line of research in international development suggests that giving directly to those in need is better.

Is cash alone sufficient?

LEO’s research on comprehensive case management has shown that pairing a person experiencing hardship with a trained social worker can have a transformative effect on the lives of those in need. In Seattle, LEO’s David Phillips and Jim Sullivan are studying the difference between groups receiving a full suite of case management and funding over time, versus solely immediate financial assistance. Another LEO study in Santa Clara, California asks similar questions.

Limitations and difficulties

EFA is seen as an innovative—if not revolutionary—approach to fighting poverty. But why? It’s comparatively low cost, easy to administer, and much easier to scale than more personnel-intensive solutions like case management. Additionally, it’s relatively easy to identify tipping-point moments in someone’s life, especially around preeminent eviction and loss of transportation or utilities.

Part of the difficulty with scaling EFA is what economists call the “wrong pockets” problem. The wrong pockets problem describes a situation in which the primary benefits of a program don’t accrue to the party who paid for it. For example, when the U.S. government helps veterans access preventative health checkups, which are shown to reduce emergency room visits to VA hospitals, the costs and savings are aligned. Whereas, in the case of Catholic Charities Chicago’s Homelessness Prevention Call Center, the program is funded by the diocese, as well as individuals and local foundations. But the “savings” are spread out among various parties, showing up in a decrease in violent crime—a social good, for sure—and fewer entries into the homeless shelter.

Another issue is that EFA is an upfront investment for a future uncertain benefit, and it’s human nature to avoid this tradeoff. While we’re 100% likely to get the root canal once we’re in excruciating pain, we’re only 50% likely to have our teeth cleaned semi-annually (and likely much lower odds for flossing and other preventative maintenance). Innovative financing mechanisms, such as impact bonds, have had success changing this dynamic. An impact bond is a performance-based contract, where upfront financing for a project is provided—if the intended results are achieved, the loan is forgiven and the project finances itself.

The silver lining

For economists, the silver lining to tragedies such as the great recession, or the pandemic, is that they can provide an opportunity to test which solutions work. In 2020, the CARES Act provided the largest influx in funding for vulnerable populations in our lifetime. LEO has taken this opportunity to partner with nonprofits from Houston to Seattle to Chicago to figure out how emergency financial assistance can help those experiencing poverty to mount a recovery, and to avoid poverty in the future. Growing evidence shows that one of the most efficient ways to fight poverty is to stop it before it begins—that a well-timed influx of cash can help how we care for the most vulnerable among us.