By Jim Sullivan, LEO Co-founder & Gilbert F. Schaefer College Professor of Economics

“Let no one ever again say that we dreamed too small.” – Fr. John Jenkins, September 23, 2005

Fr. Jenkins’ challenge to the Notre Dame community in his inaugural address factored heavily in the formation of LEO. If you’re going to start something that aims to change the way we fight poverty in America, best to do it at an institution that truly believes that by thinking big we can make the world a better place.

What I didn’t fully appreciate at the start was that, for LEO to succeed, it would take a lot more than just aiming high. We would need to find partners who were willing to do the same: take some risks, do things differently, and challenge the status quo. Fortunately, those providers are out there.

It 2014, LEO’s co-founder Bill Evans and I received a call from one of our earliest partners, Catholic Charities Fort Worth (CCFW). “We want to end poverty and need your help,” they said. That certainly counts as aiming high, but talk is cheap. Curious to learn more, we asked them what they had in mind.

Soon, Bill and I were in Fort Worth, learning about CCFW’s bold new initiative to design a client-centered solution based on their experience working with people struggling in poverty. We listened as the team shared their experiences, talked to people they serve, and even watched as CCFW staff threw teddy bears (seriously!) at each other if someone started talking about what “couldn’t be done.” It was all about dreaming of a future for their clients of what could be, about what should be.

CCFW first called this initiative its “all in” project. The thought was that they were seeing too many repeat customers, something that symbolized to them that they were failing the very people they were set up to serve. The program was designed to be free from previous constraints—limitations on the length of time clients could receive services, a narrow focus on only incremental progress, and the problems that come from implementing programs that treat the symptoms rather than the causes of poverty. Instead, CCFW wanted to create something that they believed was exactly what their clients needed: comprehensive and sustained support; a relationship with a social work team that could address basic needs while also helping clients reimagine their bigger, brighter future; and access to financial assistance to help overcome the obstacles they would inevitably confront during their journey out of poverty.

Padua—as this program eventually became known (after St. Anthony of Padua, the patron saint of the poor)—was unlike any other program LEO had seen before. We were intrigued by the innovative approach and its comprehensive nature. Understanding whether a program such as this could effectively move people out of poverty was why we created LEO in the first place.

For the past five years we have been tracking key outcomes for participants in our Padua study. Given the multi-faceted nature of the program, we considered its impact on several key outcomes including employment, earnings, government program participation, and savings. Although our analyses of key outcomes is ongoing, some promising results have already emerged.

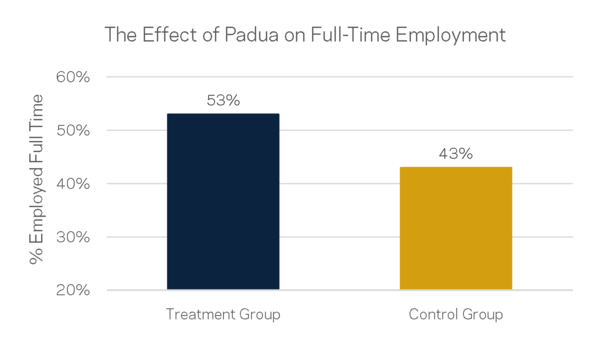

The most promising result so far is Padua’s impact on employment. After two years, 53 percent of those randomly assigned to receive Padua services had full-time employment as compared to 43 percent for the control group. That’s a 25 percent increase in full-time work, which is a much larger impact than the typical job-training program. We also find promising evidence indicating that Padua leads to increased earnings.

Another clear takeaway from our analyses is that Padua can have very different effects for different people. This is important because if an intervention is only affecting certain groups, then small or negligible effects for the entire sample might mask big effects for subgroups. In our analyses, we noticed that Padua’s effect on employment was particularly pronounced for participants who were already stably housed when they started the program. For this group, Padua increases full-time work by 36 percent. For those who were initially homeless or couch surfing, in contrast, Padua had no discernable effect on employment.

Conversations with CCFW about the program helped us understand why we see this difference. If a client enters Padua while in severe crisis—for example, they’ve been evicted and have no place to live—then the program first focuses on stabilizing their housing before working with the client to improve their labor market situation. And this is borne out in the data. Although there is no effect on employment, we find very large impacts on housing for this particularly vulnerable group. The treatment group is nearly 60 percent more likely to be stably housed two years after initial enrollment in the program.

We still have a lot to learn about Padua’s impact and we will track key outcomes for study participants for many years to come. But our initial results are already shaping our understanding of how comprehensive, sustained interventions can help people reach their dream of exiting poverty.